I had a horrendous experience two summers ago with a Strangles infection in my horse. It was a calamity of errors due to misdiagnoses (plural intentional) by several different vets, because the symptoms of the illness were “not textbook.” The misdiagnoses prolonged and exacerbated the illness. Strangles (bacterium Streptococcus equi, also known as Equine Distemper), an illness that would normally resolve itself within three weeks, dragged on for three months, escalated in severity and almost killed my horse. I won’t even go into the cost of all of this.  The vets involved had thought, in retrospect, about writing papers about the experience because it was “the weirdest thing.” As far as I know, the papers have not been written. A good friend recommended that I take it upon myself write about the experience, just to get the word out and help others that may end up in the same situation. This post will be long and involved, but I feel it’s necessary to get the details out since the situation was so unique and everything turned out to be related in the end.

The vets involved had thought, in retrospect, about writing papers about the experience because it was “the weirdest thing.” As far as I know, the papers have not been written. A good friend recommended that I take it upon myself write about the experience, just to get the word out and help others that may end up in the same situation. This post will be long and involved, but I feel it’s necessary to get the details out since the situation was so unique and everything turned out to be related in the end.

The beginning of the story actually goes back four years. I was taking riding lessons at a ranch in Elisabeth, Colorado. A horse owner at the ranch had a palomino named Joe that she needed to sell, but was having no luck. She finally told the ranch owner, Teri, that if she were to find someone who would really take good care of Joe, she would consider just giving him away.

Teri mentioned that to me, but although I’d dreamed of owning a horse all my life, it was always out of reach because of the expense, location and my admitted lack of experience. So the possibility never sank in. Fast forward several months. By this time I had gotten to know Joe, a healthy 11 year old Missouri Fox Trotter gelding. I rode him in some lessons and had developed a relationship with him due to his people-loving, big puppy, barn-clown nature. One day, as I was grooming him after a lesson, Teri said someone was coming to see Joe in a few days and they might be interested in buying him. She said, “I know you and Joe have a special relationship, so I just want to let you know that if you want him, you can have him. But you have to make your mind up quickly.” Again, the “have” part didn’t really sink in. Hours later I was at home, making dinner and thinking about what Teri said. I could HAVE him? Like, for FREE? That couldn’t be what she said. I called her and asked. Teri said, “yes, you goofball, I’ve told you that before.” That was all I needed to hear. Less than a week before my birthday, in mid-January 2011, Teri signed over the paperwork and I finally had a horse of my own.

Teri mentioned that to me, but although I’d dreamed of owning a horse all my life, it was always out of reach because of the expense, location and my admitted lack of experience. So the possibility never sank in. Fast forward several months. By this time I had gotten to know Joe, a healthy 11 year old Missouri Fox Trotter gelding. I rode him in some lessons and had developed a relationship with him due to his people-loving, big puppy, barn-clown nature. One day, as I was grooming him after a lesson, Teri said someone was coming to see Joe in a few days and they might be interested in buying him. She said, “I know you and Joe have a special relationship, so I just want to let you know that if you want him, you can have him. But you have to make your mind up quickly.” Again, the “have” part didn’t really sink in. Hours later I was at home, making dinner and thinking about what Teri said. I could HAVE him? Like, for FREE? That couldn’t be what she said. I called her and asked. Teri said, “yes, you goofball, I’ve told you that before.” That was all I needed to hear. Less than a week before my birthday, in mid-January 2011, Teri signed over the paperwork and I finally had a horse of my own.

That spring (2011), I noticed that Joe had some swollen lymph nodes in his throat in the same area where a kid would have swollen tonsils, also called the throat latch area. I mentioned it to Teri and my barn vet. Both said it could just be allergies and as long as Joe was acting healthy I shouldn’t worry. Joe’s spring physical checked out fine. A few months later I noticed some scabbing under his chin area and drainage, like a small abscess had opened. I had the vet take a look and he said it was probably caused by a hay splinter or something wedged under Joe’s tongue that had finally worked its way out. The rest of the year everything was just fine.

The next spring (2012), it happened again. Swollen lymph nodes in the throat, but no signs that Joe wasn’t feeling perfectly fine. The vet said it may be seasonable allergies. Some horses just go through little things like that. A few months later, there was the scab and a small draining abscess.

Spring of 2013 brought the same swollen nodes. Then came June of 2013. I was on vacation, just a day or two from returning home, when I received an email from my vet saying Joe had injured his right hock. The vet was convinced that there was infection in the joint. He had taken a synovial fluid sample from the joint but it was still at the lab. He wanted to do immediate surgery to clean out the joint and had Joe on antibiotics in the meantime. Soon I received an email from Teri saying Joe had injured his hock, was on stable rest for a few days and would be fine—not to worry. I emailed back telling her what the vet had said; I also emailed the vet telling him he would have to wait the extra day for lab results before I would consider surgery. I was so close to being back in town… The following day the lab results came back negative for infection: it was purely an injury.

Home again, I immediately headed over to the barn. Joe was not recovering from his injury as quickly as the vet felt he should and was thinking there may have been a break or bone spur involved. (I found out later that Joe had gone back into the pasture once his injury appeared to be improving. He was no doubt roughhousing with his pasture mate and re-injured his already weakened hock. The vet didn’t know this and thought Joe had been on stall rest the entire time.) Other than his hock injury, Joe appeared perfectly healthy. The vet recommended x-rays as soon as possible, referring me to another vet that had a mobile x-ray unit. I scheduled an appointment for the next day.

That morning I got a very early wake-up call from the barn: something was very wrong with Joe, above and beyond the hock injury. He was lethargic, looked to be in pain, was having some trouble breathing and was drooling grass-infused saliva from the mouth and nose. He was having trouble swallowing. Teri thought it may be pneumonia although his temperature was normal. Also, the previous evening there had been a horrific lightening storm at the barn, which had startled the horses during their feeding time. Joe may have inhaled some hay or was having a “choke”—when a mouthful of hay gets stuck in the throat.

I already had a vet coming that afternoon to do x-rays, so I called and asked if they could get there earlier. They did. They “tubed” Joe —forcing a rubber hose through his nose, into the throat and flushing the throat with water in the hopes that they could dislodge anything stuck. Of course, even as sick as Joe was, he fought having the hose forced through his nose, reared once or twice and ended up causing injuries to his nasal passage in the process. He bled profusely for a couple of hours, snorting blood everywhere. I was mortified but the vet said it’s not uncommon and the bleeding would eventually stop. Having an aversion to blood to begin with, I struggled to attend to him while fighting lightheadness on and off. Of course, there was a lot of cleanup afterwards as well. I was amazed how much blood there could be and yet he didn’t bleed out.

Joe seemed to be able to swallow a little better after the tubing, so the vet proceeded to x-ray the injured leg. No broken bones, no bone spurs. An additional lab test on the synovial fluid indicated that he was healing.

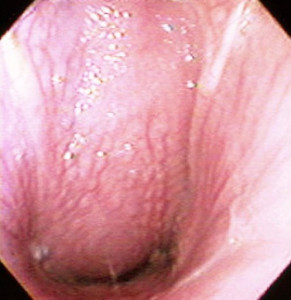

The next morning I got one of those early wake-up calls: Joe was in terrible shape, worse than ever. Again he was drooling, had the runny nose, could not eat, was lethargic and in pain. Temperature was normal. Teri told me to get out there right away, we were going to put Joe in a horse trailer to make a trip to the Equine Veterinary Clinic. At the clinic, we were directed to an examining room where he was braced into a contraption that would keep him from moving or struggling. After a lengthy explanation of what had taken place over the past 2-3 weeks, I told the vet about Joe’s history with swollen lymph nodes every spring that would drain after a couple of months. Or as I said, “open up.” That immediately caught the vet’s attention and he blurted out, wide eyed: “open up, like to the world?” Yes, that’s what I meant. He scribbled a note and then proceeded to scope Joe’s throat. This involved tranquilizing him to the point where they could, once again, force a hose up his nose. I got to watch the live camera on screen as they traveled through Joe’s throat. When they got to there area of his throat where, if he were human, would be the end of the soft palate, I could see his throat was swollen beyond recognition. It looked like an enormous lump was blocking his throat and it reminded me of strep-infected tonsils in a human. I said as much and was told that horses don’t have tonsils. The vet thought it was a tumor, most likely cancerous and located in an area where surgery was not an option. He took some biopsy samples and sent them off to be tested. While Joe still had the hose in his nose, they sprayed in some steroids and then released him from the exam room. I was left to walking him around the grounds until the tranquilizers wore off. He seemed to feel better and was able to eat some grass, which he really enjoyed.

Teri picked us both up and took us back to the barn. I had been instructed on giving pills to Joe plus my “own” rubber hose to stick up his nose and spray his throat with steroids, twice a day. Oh boy, shoving a hose up the nose of a horse, even as sick as Joe was, is at best impossible. Also, no more hay or grass for Joe—he was to be fed senior equine pellets that had been soaked in water, creating an easy-to-swallow mash. I supplemented with cool, moist shredded carrots. Teri and her family were leaving, pre-dawn, the next day for a family vacation, so I had plans to sleep out at the barn in order to administer Joe’s medications. I began researching, on the Internet, what could possibly make a horse so seriously ill, so quickly.

The next morning, just as the sun was coming up, I went into Joe’s stall to see how he’d managed over night. He was worse than ever. He was sneezing and drooling slime everywhere, mixed with some blood from the most recent tubing, had some trouble breathing, was not able to swallow, in pain, lethargic… back to the Equine Hospital. But yet, no temperature. Joe was sedated, scoped once again and I was told he was going to have to stay there in Intensive Care so they could keep a close eye on him and administer around-the-clock medications. Back to the Internet, between visits to the hospital. I just couldn’t get strep throat out of my mind, and found out that horses get their own, species-specific form of strep, called Strangles. Most articles I read about Strangles said that it should not be treated with antibiotics, it will run its own course. Recommended treatment is no treatment: let the infected nodes expand until they rupture and drain, then keep the area cleaned. The immune system will take care of the rest. The reason for no antibiotics is that they will not always kill all of the bacteria or could prevent the rupture and drainage of infected nodes. Like strep in humans, if not completely overcome, it can go systemic, lodge in other areas of the body (brain, kidneys, spinal cord, joints) and cause even more serious illness. It then becomes known as Bastard Strangles. The mortality rate of Strangles in horses is about 1%. Mortality for Bastard Strangles is about 62%.

Joe was released from the hospital (by this time it was July 2013) and appeared to be feeling better, but not completely recovered. The test results from the cancer biopsy had still not come back due to some delays I won’t explain here. I began asking if the vets thought Joe could have Strangles but was again told it wasn’t likely because the symptoms were not text book. I asked if they were testing for it “just in case,” since they’d done biopsies while scoping Joe and were already in his throat, but they said no. They were convinced it was a fast-growing tumor. Back at the ranch, I had to make sure Joe was out of his stall and walked every day (turnout time) because his legs were showing some signs of swelling, which is fairly typical for stall-bound horses. Or so we thought.

Not long after Joe’s release from the clinic, I got another one of those early morning phone calls from the barn. Joe was in terrible pain and could not walk. All four legs had swollen, especially evident in the joints. He could barely move and was in obvious pain. For the first time since this all started, he had an elevated temperature. Teri said she would get him loaded into the trailer and would meet me at the Equine Clinic. I had to get him out of the trailer and into the examining room and it was obvious he was in excruciating pain. I had to keep talking him along, encouraging, pleading and he did his best to cooperate. That last step off the ramp and onto pavement was the worst—the expression of pain on his face, lips drawn back over his teeth in agony, made my heart stop. But he kept moving, barely able to bend his legs to walk.

The vets immediately recognized it for what it was: purpura hemorrhagica. Bastard Strangles had spread to his joints and his immune system responded by causing swelling and hemorrhaging blood vessels. Now the vets were worried: Joe had been exposing other horses at not only the barn, but the Clinic, for two months. They locked him up in Quarantine, which was a concrete shed isolated from the rest of the animals on the property. He was hooked up to heavy duty antibiotics and steroids administered intravenously, 24 hours a day for seven days. I was not permitted to go within 20 feet of him and spent every day talking to him from a distance. I’d smuggle shredded carrots to him through the medical staff so he’d get a break from eating mash. They FINALLY did a culture for strangles and sent it out for testing. By this time the cancer biopsies had come back negative.

After the week in solitary confinement, the strangles test came back showing that Joe was not a “shedder” — meaning although he did have strangles, he was not spreading the organisms to other animals through his body fluids. They considered letting him go home in a few days.

Early on the Sunday morning before his anticipated release, I visited Joe. I could see a horse peacefully resting on the ground in a pen just on the other side of a trash dumpster from where Joe was incarcerated. On closer inspection I saw the horse was not breathing and there were flies and some blood on his body. I then recognized the horse as one I’d seen the day before—in Intensive Care. He’d been through colic surgery and was on IV medication when I last saw him. Now he was dead in an outdoor pen, his nose propped peacefully on one extended foreleg like he’d just nodded off to sleep. Apparently the surgery had not gone as well as they’d hoped. He had been in extreme pain and the owner opted for euthanasia.

That’s when I knew I’d have to give up Joe. Everything that is alive… will eventually die. After going through three full months of one emergency after another, worry, stress and more worry and stress, I realized that I just don’t have the backbone to one day deal with the death of my dream come true.

August 2013 saw Joe back at the barn. After three months of eating senior mash and the loss of at least 100 pounds, he was finally allowed to eat water-soaked and softened hay. He was in heaven—real food, at last. He was to be kept on antibiotics for six weeks. I told Teri about my decision to give Joe back to her and explained why. She understood and made it as easy as possible. Clearing out my tack stall was excruciating. I was so traumatized by the entire event that I gave away all of my horse-related apparel and tack and only kept the major things: my saddle, bareback pad, blanket and bridle. They are still packed away in boxes in the garage.

It’s been almost two years since I gave Joe back, and finally got up the courage to visit him about a month ago. He recognized me from a great distance and stared intently as I walked towards his paddock. He began nickering as I got closer to let me know he recognized me as a friend, which of course made me teary-eyed. He walked with me, shoulder-to-shoulder, to the gate so I could get a halter on him and take him up to the barn for some grooming. It was like old times and I left feeling like I’ve finally made some progress in getting over the events of that summer and mourning the loss of a dream come true. But seeing Joe healthy and happy once again is heartening and apparently he will be immune from Strangles, at least for the next five years to so. In a couple of weeks I’ll return to riding lessons, just to be around horses and the ranch again. I’ll continue to visit Joe and bring him treats.

I hope this post helps prevent someone from going through what I what I did. If the vets had been able to think outside the box with Joe’s symptoms, if they had taken this novice’s questions about Strangles seriously, if Joe hadn’t been given antibiotics for an injury, if I had been more insistent on being taken seriously, if, if, if…

I hope this post helps prevent someone from going through what I what I did. If the vets had been able to think outside the box with Joe’s symptoms, if they had taken this novice’s questions about Strangles seriously, if Joe hadn’t been given antibiotics for an injury, if I had been more insistent on being taken seriously, if, if, if…

Conclusion

This is what I feel happened. I am not a vet. I have no medical training. So take this with a salt lick:

My thought is that Joe carried Strangles for years, but his immune system was able to keep it in check. The swollen nodes every spring, that ruptured in summer, were a symptom—a clue. Why the symptoms would happen in the spring, as opposed to any other time of the year, is unknown to me. But I can also say that every spring Joe thinks he’s a stallion and his behavior becomes impossible for a couple of months, so that may somehow be related. Then Joe injured his hock. It was a bad sprain and his immune system was redirected to that area of his body and away from the Strep. That allowed the Strep bacteria, an opportunistic pathogen, to grow unchecked. The antibiotics only made things worse, and it was all downhill from there. If Joe had injured his hock at a different time of the year, this may not have happened at all.

At least he’s alive.

I really appreciated your story. Our horse was recently diagnosed with Strangles, but thankfully was not put on antibiotics. We let the strangles run its course and she was doing better for a few weeks. However, she may now have bastard strangles (we are waiting for test results to come back) as she is having other symptoms. She is on heavy duty antibiotics now, but I’m wondering if you remember what antibiotics were prescribed for your horse? I’m assuming the steroids were given for the swelling? If they served another purpose, I’d be interested to hear what that was. I want to do everything for our horse possible. Thank you for your time.

I don’t remember what the antibiotic was. When he was in quarantine they had him hooked up to an IV for a week. I don’t know about the steroids, but it seems they would have been included. Once he was back home we had to give him these huge antibiotic pills, 6 three times a day, for an entire month. My vet wanted to put him on some special super duper antibiotic that had to be specially ordered and costs about $1,000 per dose. We opted for the pills and he’s been fine ever since (it’s been 6 years). I did give him probiotics, knowing what antibiotics do to gut health. That was a tough summer. Hopefully you have really good vets, you’re close to horse country so I’m thinking you do. Best of luck to you and your horse!

Hi there,

Can you remember if he was exposed to strangles (either another horse or vaccine or from a horse that just got the intranasal vaccine where it would have come in contact with him, ) at any time? This would have started it all.

Also, do you remember what test it was that confirmed he was not contagious ? Thank you for this story, I am going thru this now, where the horse was misdiagnosed and we were told it was lymphangitis / cellulitis? She was put on 2 types of Antibiotics for 2 weeks. She is 27 and is having a super rough go, but she is still fighting. My theory is that when the owner purchased her (300-400 lbs underweight) 7 years ago, she had had strangles at some point. it Harbored in her and having Cushings (went untreated for a few years) came out. It is clearly now Bastard Strangles. Did you put Joe on any Nsaids? Dawn seems in pain, and when given Banamine she starts eating again and moving around. The Vet does not fully believe my theory…….. so frustrated!

Hi Pam, so sorry you’re going through this! Joe was given to me, he had been at the same stables for five years before that so he must have been exposed prior to that and was a carrier for years. But he never had full symptoms until his hock injury threw his body into overload. The vets, once they finally acknowledged that Joe had strangles, did some sort of test on (probably) nasal mucus which showed he was not a shedder. They didn’t tell me what the test was called. Other horses at the stables had been exposed to him for months while he was sick, some of them even cleaned his face for him, and none of them got sick.

I don’t recall Nsaids, but my guess is they would have given him some when he was on the IV antibiotics for a week. He was in terrible pain when he had stocked up. That all happened in 2013. I was just in touch with his current owner yesterday and they’re celebrating his 21st birthday! No problems since the situation I had, except for a little arthritis, but he’s still being ridden when he’s up to it. My vet was going to write a paper on Joe’s case because he and the other vets didn’t believe it either! I don’t know if he followed through, he’s retired now, but his name is Dale Rice and he’s in Elizabeth, CO. Best of luck to you and your horse. Maybe you can tell your vet about my experience? I don’t know if Dale is still around, but he’d probably talk to your vet if he is.

Update: https://threepeaksveterinary.com/ (303) 683-4634

thank you so much! this is helpful. It is a mystery but heartbreaking to see her go thru this. W might have to put her down, but every time we discuss it she perks up and we keep trying.

Thanks

Pam